Waterpipe

This page was last edited on at

Background

What is waterpipe?

Waterpipe has different names in different countries such as narghileh, shisha, hookah, hubble-bubble, or goza.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines waterpipe tobacco smoking (WTS) as “a form of tobacco consumption that utilizes a single or multi-stemmed instrument to smoke flavoured or non-flavoured tobacco, where smoke is designed to pass through water or other liquid before reaching the smoker”.1 Some countries have developed their own definition of waterpipe tobacco smoking (WTS).2

The origin of WTS is somewhat unclear. In the late 19th century, it was popular among older men in the Middle East but with the introduction of sweetened and flavoured tobacco in the early 1990’s, waterpipe use surged among youth, and expanded globally, through universities and schools.34

Social acceptability of waterpipe use has increased, due to the growth of ‘café culture’ in the Middle East and globally, becoming the focus of social gatherings of young people, as a waterpipe can be shared by a group of friends over an extended time, with a slow puff rate. Tourists have taken the waterpipe habit back to their countries, and expatriates from the Middle East have opened waterpipe cafés and restaurants around the world.1456In this way waterpipe has spread beyond the Middle East and become integrated into the global tobacco market.7 While there are restrictions on tobacco advertising in other regions, products have been promoted throughout the Middle East via satellite television, internet and social media. As these media are largely unregulated the industry is able to circumvent most advertising bans (see below for more on product regulation).561

Transnational tobacco company interests

Historically, transnational tobacco companies had little interest in waterpipe tobacco smoking. A review of tobacco industry documents showed no focus on waterpipe tobacco or its accessories, except for some ‘waterpipe-inspired’ products that did not become mainstream in the market.8

This was the case until 2012, when Japan Tobacco International (JTI) acquired Egyptian company Al Nakhla.9 At the time Al Nakhla was globally the largest company manufacturing waterpipe tobacco products.10 However, even this was perceived as a strategy to enhance the sale of cigarettes.8

In 2019, Philip Morris International (PMI) filed a patent ‘Shisha device for heating a substrate without combustion.’8 However, as of 2023, this product had not yet appeared on the market.

- See Waterpipe market below for details on companies, brands and market shares

Use

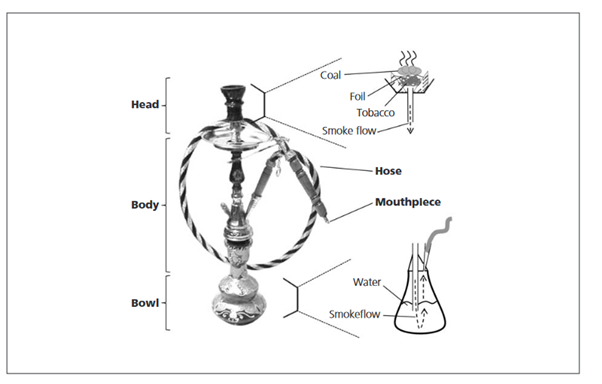

Image 1: Waterpipe device (Source: Waterpipe Briefing, National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training/Jawad et al 2013)1112

Waterpipe tobacco is smoked using a device like that in image 1. As the smoker draws from the mouthpiece, a piece of lit charcoal heats the waterpipe tobacco leaf within the head of the apparatus. This heat generates smoke that travels through the device’s body and enters the water-filled bowl. By inhaling through the hose attached to the top of the bowl, the smoker pulls the smoke through the water, resulting in bubbles, before finally inhaling the smoke via the mouthpiece. Typically, the head is filled with flavoured and sweetened, and it is separated from the charcoal by a perforated aluminium foil. While the specific design and characteristics may vary across different regions, the fundamental principle remains consistent: the smoke is filtered through water.5

E-hookahs or e-shisha or hookah pens are not waterpipe devices as they do not involve burning charcoal. These are classified as electronic nicotine devices, similar to e-cigarettes, where a sweetened liquid is electrically heated creating an aerosol to be inhaled.1

- For more information on e-cigarettes and other product types see Tobacco Industry Product Terminology

The role of flavour

The traditional type of waterpipe tobacco smoking (WTS) uses unflavoured types of leaf (Ajami, Tumbak, or Jurak). However, since the 1990s flavoured tobacco has become more popular.561

The most common type is Maasel (or Mo’assel), or ‘honeyed’ tobacco, which consists of one-third tobacco and two-thirds honey and fruit flavours, usually a combination of tobacco, molasses, glycerine and fruit flavours.13. A review looking at waterpipe use in the USA, Canada and the UK has shown that young adults use waterpipe mainly for its appealing flavours, always preferring it over other tobacco products.14 A study among , adults in Lebanon indicated that the introduction of novel tobacco flavours contributed to people initiating WTS and increased its use.15 Similarly, a study from Iran indicated that the wide variety of flavours has as well contributors to the increase in prevalence of smoking among youth and women. The different flavours were considered ‘tempting’.16

- For information on the appeal of flavoured tobacco products see Flavoured and Menthol Tobacco

Health effects

Evidence shows that waterpipe, like other tobacco and nicotine products, is addictive.17

As with cigarettes and rolling tobacco the smoke of waterpipe is toxic and carcinogenic. One study identified 27 known or suspected carcinogens. 18As a waterpipe is often shared, it is also a mode of transmission for communicable diseases, a particular concern during the COVID-19 pandemic.19 Consequently, waterpipe has both short-term and long-term harmful health impacts on people who use it, and additional harms for those exposed to second-hand smoke.1202122

Among many groups of users there is a belief that the smoke of waterpipe is filtered in water, making it less harmful than cigarette smoking. This perception has contributed to a growing popularity and acceptance.561 For example research from the UK found that:

“[w]aterpipe was perceived to be safer than cigarette smoking due to the pleasant odour, fruity flavours, and belief that water filtered the toxins.”23

However, waterpipe contains similar or greater levels of toxic substances, leading to the same cellular effects as conventional products, leading to pulmonary and arterial diseases.1824

Prevalence

A 2018 systematic review, which included 129 studies from 68 countries, found that use of waterpipe was highest among adults in the Eastern Mediterranean region (EMR). However, among youth, prevalence was similar in Europe and EMR. Comparing WTS between adults and youth, globally the study reveals that smoking is higher among youth.25

A WHO advisory note about waterpipe, published in 2015, indicated that although waterpipe smoking was traditionally associated with the Eastern Mediterranean region, Southeast Asia and Northern Africa, its use is growing globally among youth and adults of both genders. Use is particularly increasing among schoolchildren and university students. Research reported in the WHO advisory note 6 and a study from Lebanon indicates that the shape, colour and size of the apparatus contributed to the popularity of WTS product mainly among women.26

Africa

Research in South Africa from 2012, shows that 20% of poor high-school students reported using waterpipe daily, and 60% reported ever having used one.27 A study in Western Cape from 2013, reported higher figures: 40% current use, and 70% ever use.28 Even among medical students, use may be relatively high; a study in Pretoria in 2010 found that nearly 20% of participants had used a waterpipe at some time.29

The Americas

Although there is limited research on waterpipe in Latin America, some has been conducted in the United States (US) and Canada. In US a national study of 104,434 university students, published in 2014, shows that after cigarette smoking, waterpipe smoking was the most frequent form of tobacco use (8.4%, compared to 29.7% for cigarettes), and over 30% reported using waterpipe at some time.30 In Canada, although cigarette smoking among young people had significantly decreased, waterpipe use increased by 2.6% among young people between 2006 and 2010.31

Eastern Mediterranean

This region has the highest prevalence of waterpipe use. Studies (1999 – 2008) suggest that waterpipe use was more frequent than cigarette smoking among children aged 13–15 in most countries of the region.32 It also increased in multiple countries, with prevalence ranging from 9% to 15%.33

Europe

Evidence compiled in 2012 showed that, among people aged 15 years or over, 16% had tried waterpipe at least once. Studies suggest waterpipe prevalence ranging from 35-40% in Latvia, Estonia, and Lithuania, but below 10% in Malta, Spain, Portugal, and Ireland. Use was growing sharply in Austria, the Czech Republic and Luxembourg.34 In England, data from 2013 indicated that for people aged 16-18 the level of waterpipe smoking was low, at 3%.35

However, a study looking at adult smoking in England using a nationally representative cross-sectional survey found that since then pipe, cigar or waterpipe smoking increased five times – from around 150, 000in 2013 to over 770, 000 in 2023. Cigars was the most used of the three product types, closely followed by waterpipe, and the increase was higher among young adults.36.

South-East Asia

Studies (2008 – 2011) suggest that waterpipe prevalence among men was just over 1% in Bangladesh, and in India, and much lower in in Indonesia and in Thailand (0.3%). Fewer than 1% of women use waterpipe in India Bangladesh, Indonesia, and Thailand.3738 However, waterpipe “hookah” bars and restaurants are becoming increasingly common and are most often frequented by young people.

Western Pacific

Waterpipe is called “bong” and is different in design from the popular Middle Eastern waterpipe, and therefore is often not included in waterpipe studies. It can be made of bamboo, metal or glass and is used in China, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Myanmar, and Vietnam. In 2010 in Vietnam around 13% of males aged or over 15 used bong.37

Regulation

In many higher income countries, waterpipe products are exempted from tobacco control policies. In many lower income countries, even if there is a policy, enforcement is very weak. Although flavouring is a major factor in the appeal to young people, flavour bans often do not cover waterpipe tobacco products. Consequently, the use of waterpipe has increased globally, largely unchecked.5614

The WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC) identifies tobacco products as “products entirely or partly made of the leaf tobacco as raw material which are manufactured to be used for smoking, sucking, chewing or snuffing”.39 This definition covers waterpipe tobacco products. WHO FCTC issued COP decisions specifically for waterpipe tobacco control:

- At COP3 in 2008, Parties were invited to consider introducing health warnings and messages on tobacco packages, including waterpipe, and to use innovative measures requiring health warnings and messages to be printed on instruments used for waterpipe smoking.40

- At COP6 in 2014, Parties were invited to strengthen the implementation of WHO FCTC on waterpipe, including conducting surveillance of its use and research on its market. This decision also invited the Secretariat of the Convention to work with the WHO to support countries in waterpipe control.41

- At COP7 in 2016, more detailed instructions were given to Parties, including to ban the use of flavourings in waterpipe tobacco products.42

- At COP8 in 2018, there is a decision on the implementation of Articles 9 and 10 of the WHO FCTC (Regulation of contents and disclosure of tobacco products, including waterpipe, smokeless tobacco and heated tobacco products), including the establishment of an expert group to examine the reasons for low implementation of Articles 9 and 10 of the Convention.43

The full list of articles covering waterpipe are listed in the Fact sheet: Waterpipe tobacco smoking & health.1

In January 2016, the Secretariat of the WHO FCTC signed a Memorandum of Understanding with The American University of Beirut making it the global knowledge hub for WTS, in particular with respect to education, research, and the dissemination of information that contributes to the implementation of the Convention. 44

In 2018, the WTS knowledge hub submitted a report to the WHO FCTC COP8 that summarized Parties’ regulations concerning waterpipe.45 This report was updated in 2022, and found that, of the 90 countries reviewed, over half (47) had policies relating to waterpipe.2 The majority of policies, nearly 45%, were in Europe and around 21% in EMR.2

For up-to-date information on tobacco regulation, see the Tobacco Control Laws website, published by the Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids (CTFK).

Information on progress by parties can be found in the FCTC Implementation database.

During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, many countries temporarily banned the use of waterpipe as part of their efforts to stop the spread of the infection.19 In EMR alone, 17 countries banned waterpipe tobacco use in public places.46

Waterpipe, along with heated tobacco products, had been exempted from the EU flavour ban, stipulated by the 2014 European Tobacco Products Directive (TPD) and implemented in 2020. A new directive was issued in 2022 and came into force in 2023. This removed the exemption, bringing regulation of these products in line with cigarettes and hand rolled tobacco.4748 This means that waterpipe tobacco with a “characterising flavour” can no longer be sold legally in the EU. For more information see Menthol Cigarettes: Industry Interference in the EU and UK.

Waterpipe market

According to advocacy group It’s Still Tobacco, the region with the largest global market share of WTS is the Middle East and Africa (MENA), a range estimate for the two years2016-2017 to be 54% to 69% in.49

The WTS market is still concentrated in the Middle East and Africa, followed by Europe.50 Market analysis company Valuates estimated that as of 2022 the global WTS market was worth over US$ 800 million, forecast to nearly double by 2029.50

Market research company Euromonitor International publishes data on waterpipe, as part of the broader pipe tobacco category. It is therefore hard to estimate global market shares specifically for waterpipe tobacco. However, it is possible to identify specific waterpipe brands in the data. In 2022, JTI held the largest share with Al Nakhla, making up nearly 13% of the entire pipe tobacco market, followed by Al Fakher and Eastern brands (including Moassel) at around 12% and 8% respectively.51

Tobacco industry interference

The waterpipe industry is multidimensional, composed of both tobacco and non-tobacco actors, including third parties. Interference can therefore be less obvious, making it difficult to develop effective WTS policy.52 However, there is some evidence of the tactics used by the industry and its allies.

Tobacco industry tactics used to interfere with and undermine regulation relating to waterpipe include:

Use of third parties

The third-party technique includes creating, funding and empowering allies and front groups.

The public representation of the WT industry primarily revolves around the hospitality sector (waterpipe cafes, bars, and restaurants).49 Products are promoted online by users via social media, rather than WT companies.49 A study from Lebanon indicates that, following the passage of the tobacco control law, enforcement of a ban on indoor smoking came to a halt due to the lobbying of policy makers by establishments where waterpipe was available.53

In 2012, the hospitality sector in Lebanon commissioned Ernst & Young (now EY) to evaluate the effects of the smoke-free law on their financial revenue and impact on employment.4954

Spreading misleading information

Waterpipe companies have published misleading information, including on the risks of tobacco products.

A study of 16 company websites indicated that most (n=12) published misleading marketing information This was mostly prominent among non-MENA companies (n=8) compared to MENA companies’ websites (n=4). Several companies in Jordan (Al-Rayan, Al-Tawareg, Al-Waha, and Mazaya) were found to have disseminated misleading information on the quality and safety of WTS.49 WTS charcoal companies in particular published misleading information about charcoal being ‘100% natural’ and ‘free of chemicals’.49

Another study looking at marketing materials at a European trade fair, and from the MENA region, found the prevailing message was that waterpipe is less risky compared to cigarettes.55

Industry science

Al Fakher Tobacco Trading LLC, the second largest WT company, has a ‘shisha science’ section on its website and publishes its own research. A poster of a study published on its page indicates that the paper was presented at the CORESTA Smoke Technology Conference, in 2019. The study argues that a comparisons of Total Particulate Matter (TPM) yields between waterpipe and cigarettes do not provide meaningful information to inform an assessment of relative risk of its products.56

For information on science websites of transnational tobacco companies, see:

Illicit trade

Although cigarettes form most of the illicit tobacco trade, there is some evidence of illicit trade relating to waterpipe, specifically in the Eastern Mediterranean and South-East Asian regions.491.

Research from Turkey indicates that the majority (up to 99%) of waterpipe tobacco is illicitly traded, reflecting the significance of the informal economy in the waterpipe tobacco market.57 The illicit products are from both unauthorized domestic production, and increasingly tobacco smuggled from other countries, reported to taste better than locally manufactured products.58

OLAF, the European anti-fraud office, has identified suspicious shipments of waterpipe tobacco heading into Europe. In 2022, OLAF detected a truck carrying 20,000 kg of waterpipe tobacco as it was leaving Türkiye on its way to Denmark.59

Tax evasion

There have been some documented cases of the under reporting of imports and exports of waterpipe tobacco, in order to evade tax.

In 2022, New Zealand changed its taxation law related to WTS to base it on product weight rather than the content declared by importers, as the customs authority suspected that some importers had been under-declaring tobacco content in order to avoid paying tax. 60

In 2023, the Mozambique the tax authority seized two containers of waterpipe tobacco, reporting the lack of a proper declaration for taxes and other customs fees.61

Relevant Links

- WHO FCTC Knowledge Hub for Waterpipe Tobacco Smoking

- Virginia Commonwealth University Center for the Study of Tobacco Products video Addressing the Myths of Hookah

TobaccoTactics Resources

TCRG Research

Waterpipe tobacco smoking (WTS) control policies: global analysis of available legislation and equity considerations, H. Alaouie, R.S. Krishnamurthy, M. Tleis, L. El Kadi, R.A. Afifi, R. Nakkash, Tobacco Control, 2022, 31(2):187-197. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056550