Targeting Women and Girls

This page was last edited on at

Introduction

In 1921 a bill was proposed in the US congress to ban women from smoking in the District of Columbia. Yet, as Amos and Haglund note, within a few decades the idea of women smoking was not only acceptable but desirable. As they describe:

“This was due not only to the dramatic changes in the social and economic status of women over this period, but also to the way in which the tobacco industry capitalised on changing social attitudes towards women by promoting smoking as a symbol of emancipation, a “torch of freedom”.1

The industry has long marketed smoking as a form of emancipation for women and a way to enhance their personal appeal. The specifics of the campaigns change from country to country and over time but the industry’s general approach has remained constant.2 And as the WHO said: “Selling tobacco products to women is currently the largest product-marketing opportunity in the world.”3 Some of these campaigns are set out in more detail below.

Tobacco companies have seized upon the opportunities offered by social media to project familiar images to the female market. For instance, an investigation by The Bureau of Investigative Journalism found British American Tobacco had set aside £1bn to use social media platforms to reach new markets – young women among them. It quoted one 18-year-old Swede who said half the girls in his class used the Lyft nicotine pouch which had been heavily promoted on TikTok.4The increased use of social media, and in particular young attractive influencers, has led to calls for the owners of these platforms to enforce tobacco control legislation.56

Meanwhile, when not selling nicotine products directly, the tobacco industry is always thinking about gender issues as a vehicle for engaging with consumers and policymakers. As an example, research published in Tobacco Control found that Philip Morris International (PMI) and British American Tobacco (BAT) attempted to co-opt International Women’s Day in 2019. The researchers analysed twitter activity from those two companies to show how it tried to capitalise on themes such as women’s equality, gender empowerment and equal pay. The authors say:

“This attempt to embrace women’s equality is the latest example of how tobacco industry marketing has sought to use emerging cultural contexts and reference points to build positive associations with smoking as a feminist act. The media channels may have changed, but the strategy is the same: harness women’s aspirations to advance to sell more tobacco.”7

There is more detail below on how the tobacco industry uses corporate social responsibility activity to target women.

Case study on plain packaging fightback

In 2011, with restrictions on advertisements for cigarettes and the upcoming rules for Plain Packaging, the industry was desperately looking for new ways to reach the public and potential customers. Women, who smoke less than men globally, are a key demographic for tobacco companies.8 When Kate Moss walked down a Parisian catwalk with a cigarette in her first appearance in three years, for Louis Vuitton in the Louvre – on No Smoking Day – this was widely understood as a message that smoking was back in fashion.9 Tobacco companies have identified packaging and brand design as important ways to appeal to women. As a Philip Morris executive put it in 1992:10

“Throughout all our packaging qualitative research, we continue to validate that women are particularly involved with the aesthetics of packaging …we sense that women are a primary target for our innovative packaging task, and that more fashionable feminine packaging can enhance the relevance of some of our brands”.

Image 1: A photo of Glamour Pinks Superslims (left), sold by Gallaher (JTI) with pink and “slim” packaging designed to imitate that of a lipstick (right). (source: Tobacco Tactics)

Smoking and girls

According to the Tobacco Atlas, 175 million women worldwide are regular smokers. Half of female smokers live in high human development index (HDI) countries, 8 Contrary to the previous trend of young men exceeding women as smokers, girls started to overtake boys as smokers in the 1990s. In the UK in 2004, 26% of 15-year-old girls smoked, compared to 16% of boys.11 The gap has narrowed since, according to ASH statistics, with 5% of both boys and girls aged 15 being regular smokers in the UK in 2018.12

Slim cigarettes case study

In August 2011, Imperial Tobacco (now Imperial Brands) became the third major cigarette supplier to launch a “stylish new cigarette brand”: Richmond Superslims. Promoted as the first “superslim” brand in the value-price cigarette sector, the standard pack is embossed with a “stylish pink design”, “clearly designed to appeal to female smokers” reports The Grocer (Image 1).13

Image 2: A newspaper ad detailing the release of new “feminine” brands in the UK’s The Grocer retailer newspaper. (source: The Grocer)13

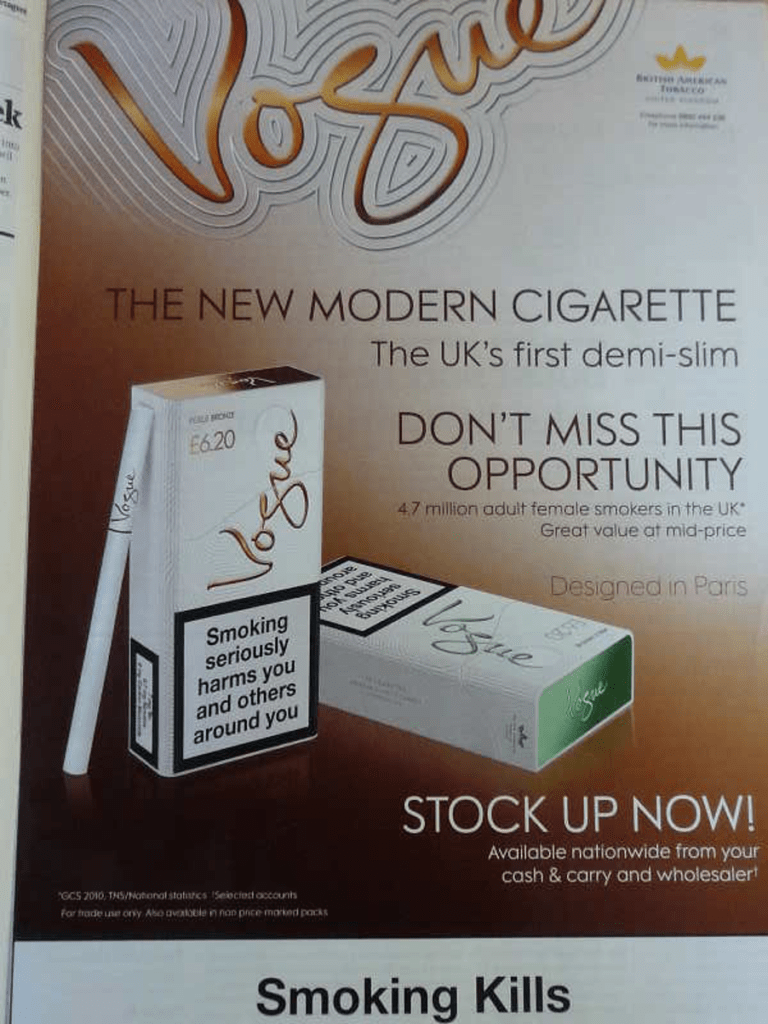

Each of the three other largest transnational tobacco companies at the time also launched female-targeted brands around the same time. Leading the trend was Japan Tobacco International (JTI), which launched its Silk Cut brand in new purple “perfume-shaped” packaging. Action on Smoking and Health (ASH) UK criticised the release as an “intentional” targeting of young women, and that to describe a product that can kill in this way is totally unacceptable”.14 In April 2011, British American Tobacco (BAT) introduced Vogue Perle, described as “the UK’s first demi-slim cigarette” (Image 3).15 Philip Morris launched Virginia S by Raffles in May 201116 and Japan Tobacco International brought out limited edition ‘V-shaped’ packs of Silk Cut a month later.17

Image 3: A photo of an advertisement for BAT’s Vogue “demi-slim” cigarettes, which it claims are smoked by “4.7 million adult female smokers in the UK”. (source: Tobacco Tactics)

Cancer Research UK reported that the advertising agency Saatchi and Saatchi analysed the design of the Vogue packets as being particularly appealing to women:18

“They evoke the classic days of smoking – Jean Luc Godard’s À bout de souffle comes to mind… The smoker feels like a French movie star, as opposed to an addict. And the price premium (£6.20) keeps the ‘vagabonds’ away. Altogether, Vogue is trying to capitalise on a woman’s desire to feel beautiful to sell their cigarettes, which is sad because they can only destroy it”.

Cancer Research UK, doctors and campaign group Fresh, Smoke Free North East were appalled by these new lines of cigarettes. “Young women are obsessed with fashion and staying slim and this is exactly the message this pack is trying to give”, commented Dr Shonag Mackenzie, consultant obstetrician at Wansbeck Hospital in Northumberland to retail magazine The Grocer.19 Dr Mackenzie added: “It is young teenage girls who don’t yet smoke but are probably experimenting who are most likely to be influenced by this”.19

British American Tobacco (BAT) defended itself against claims it “downplayed” the health risks associated with smoking in favour of the “trappings of style, supermodels and staying slim”.19 In response to the criticisms, the company said it did not encourage any individual to start smoking and used the free choice argument. “Adult smokers have different tastes and preferences and we set out to meet them with our portfolio of brands,” BAT Head of Corporate and Regulatory Affairs Ian Robertson told The Grocer. “If adult women who are aware of the health risks associated with tobacco choose to smoke, then that is a personal choice”, he added.19

Slimmer cigarettes will be “big money earners”

In December 2011, Retail Newsagent magazine ran the headline that “slimmer cigarettes will be big money earners”. The magazine noted that independent shops “still stand to make a profit on slimmer cigarettes targeted at women smokers, according to British American Tobacco.2021

Smoking and weight loss

Research confirms the perceived links between feminine branding, harmfulness and weight control. Smokers wrongly believe that certain words, such as the names of colours, and long, slim cigarettes mean the brand is less harmful, according to a 2011 study published in Addiction that included 8,000 people. About one-fifth of those smokers thought that “silver”, “gold” and “white” brands are less harmful to smoke than “black” or “red” brands. Professor David Hammond, a tobacco industry expert at Waterloo University, Ontario and one of the researchers on the study, said that the study provides evidence for further regulation: “The findings highlight the deceptive potential of ‘slim’ cigarette brands targeted primarily at young women”.22

Female-branded packs are associated with a greater number of positive attributes including glamour, slimness and attractiveness. Furthermore, those looking at female-oriented cigarette packs branded with words such as “slim” and “vogue” are more likely to believe smoking helps people control their appetite compared with those viewing plain packaging. Weight control issues are an important predictor of smoking among girls according to a Canadian study of 500 young women, also published in Tobacco Control in April 2011.23

However, the fact that the industry markets a connection between smoking and slimming is not as strange as it seems, as is shown by recent research into internal industry documents dating from 1949 to 1999. Tobacco companies have successfully used several strategies over the past 50 years to convince people that smoking makes you thin. British and American tobacco companies deliberately added powerful appetite-suppressing chemicals to cigarettes to attract people worried about their weight.24

Tobacco giants Philip Morris and British American Tobacco added appetite suppressants to cigarettes. Four other major companies tested potential chemicals including tartaric acid, a known appetite suppressant, in the 1960s, which was later banned from the market in 1977 by the US FDA.24

Professor Hammond told the Independent:25

“We know the industry explored ways to exploit concerns about weight loss back in the Sixties, because they knew it was an issue that concerned women, who they wanted to recruit as smokers. We don’t know if appetite-suppressing molecules are still added, because compliance with additive regulations is poor and sensitive internal documents are usually shredded”.

Tobacco CSR and women

Tobacco companies also seek to appropriate women’s empowerment narratives in their corporate social responsibility (CSR) strategies. CSR helps the industry build a positive reputation for itself, gain access to policymakers and divide sceptics, all while continuing to target consumers with lethal products.

The introduction of cigarettes targeted at women coincided with a public outcry about British American Tobacco (BAT) sponsoring the academic careers of four Afghan girls. In May 2011, Durham University was criticised for accepting a GB£125,000 donation towards the Chancellor’s “Scholarships for Afghan Women” appeal. The appeal assisted women to come to Durham from Kabul University to study their postgraduate degrees for five years.

Cancer Research UK argued that BAT’s Vogue advertising puts this sponsorship in a different light, because it shows the real nature of BAT’s concern for women: “The tobacco industry is energetically fighting against the idea of plain packaging because they fear that it will work – and so hurt their profits”.19

A group of concerned academics told the Durham Students Union (DSU) newspaper, Palatinate:26

“The poor judgement in taking funding from the profits of a universally-maligned tobacco giant speaks volumes for the contempt that the university’s leaders and fundraisers have for the ethos and values of this university and its staff and students.”

Anti-smoking charity ASH also criticised the donation: “There’s no stunt they won’t pull to try to look like responsible citizens. The truth is they deal in death”.26

A spokesperson for BAT argued the company had not donated the money in a bid to encourage Afghan women to start smoking. She told The Northern Echo it was all above the board, as a part of the company’s corporate responsibility programme.26

- Read more about industry funding of universities on CSR: Education.

This single example is part of a larger trend of the industry co-opting the narrative of women’s empowerment in sustainability/CSR reports. Ceylon Tobacco Company (subsidiary of BAT) states that one of the goals of its Sustainable Agricultural Development Programme (SADP) in Sri Lanka is “empowering women and recognising their significant role in each household”.27 And in 2019, Philip Morris International (PMI) paid the Jaime V. Ongpin Foundation, a Philippine NGO, US$2,171,005 as part of a programme to “reduce nationwide poverty” by “empowering women” and “effectively responding to emergency situations”.28

- Read more about how the tobacco industry frames tobacco cultivation as “women’s empowerment” on our Tobacco Farming